In the long history of Bristol as a trading port, the transatlantic traffic in enslaved Africans lasted a relatively short time. But it was of crucial economic importance to the city.

What was Bristol like before the transatlantic traffic in enslaved Africans?

Bristol has been a trading port for 1,000 years. From the early 1300s it was the second largest port in England after London. Trade at this time was based mainly on the woollen cloth produced in the surrounding counties of Somerset, Gloucestershire, Devon and Dorset.

To support the expansion of trade, the shipbuilding and financial industries grew, as well as a network of merchants with contacts in different countries. Local people and businesses produced goods to trade. Bristol’s merchants were keen, and always looking for new markets. When the opportunity came to join the developing trade to Africa and the Americas, the city was well-prepared.

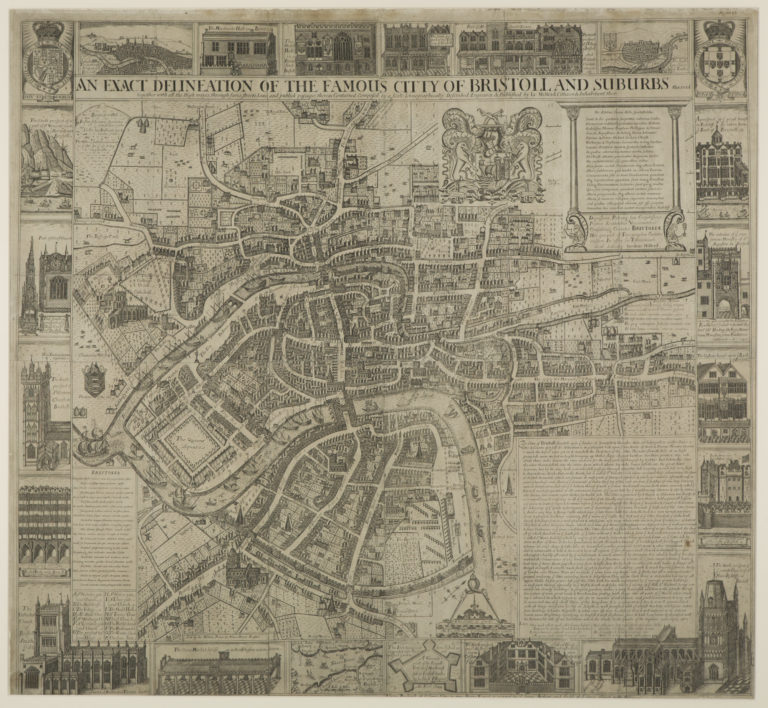

Pictured here is The Citty of Bristoll by James Millerd, 1673. It shows the River Frome behind the area of Bristol known as the Marsh and the River Avon, the main channel running through the city.

By the beginning of the 1600s, when it was still a great regional port, Bristol traded mainly with Ireland, France, Spain and Portugal. It also had links with North Africa’s Barbary Coast, the Atlantic islands of Madeira and the Azores (which were then Portuguese), and the Canaries (which were then Spanish).

European trading partners included Hamburg in Germany, Venice in Italy, Holland and the Baltic Sea area (in north eastern Europe). Woollen cloth was the city’s main export along with coal, lead and animal hides. Wine, salt, olive oil, grain and timber were the major products coming in to Bristol.

Bristol also traded with North America and the islands of the Caribbean. From the 1660s tobacco, sugar and other raw materials from the Caribbean and America were coming to Bristol in large quantities. Twenty years later, about a third of all ships sailing into Bristol were involved in trade with the Caribbean and America.

Merchants, such as Sir Robert Yeamans, pictured here, became wealthy through early involvement in the Caribbean trade. He also played a significant role in Bristol life serving at various times as Sheriff, Mayor and Chief Magistrate.

What was West Africa like before the transatlantic traffic in enslaved Africans?

The first Europeans to explore Africa knew and understood little of the continent or its peoples. Convinced of their own superiority, most failed to acknowledge the sophistication of many African societies. The political organisation across Africa ranged from small subsistence economies to sophisticated empires. Its cultures and civilisations developed and flourished, from the ancient Egyptian empire to the Asante kingdom. The Islamic Mali empire, dating from around 900 years ago, was known throughout the Muslim and Christian world as a great centre of learning, artistic creativity and wealth.

Communities in West Africa were involved in an important trade route northwards across the Sahara Desert, from about the 8th century. They dealt with Islamic traders, exchanging local products such as gold, ivory, salt and cloth for horses and other goods. The trans-Saharan trade also included enslaved Africans, who were taken to North Africa and the Moorish kingdoms of Southern Spain, as household servants. Benin (now part of Nigeria), developing from about 1400, was one of the great city-states of Africa. It was ruled by an oba or king and was a centre of industry and art, linked in to a trade network that covered Africa, Asia and Europe.

An artistic culture flourished, based on art made for the oba, who was considered divine. Specialist craftsmen worked only for the royal court. The guild of brass workers made, amongst other items, brass heads for the royal shrines and brass plaques for the palace walls, art that astonished Europeans when they first saw it in 1897.

“Great Benin…is larger than Lisbon… The city is so well governed that theft is unknown and the people live in such security that they have no doors to their houses.”

Lourenço Pinto, Portuguese ship’s captain, 1694

How and why were plantations set up in the Caribbean?

Plantations run by British landowners in the Caribbean needed large numbers of cheap, reliable labour to produce profitable commodities such as sugar, rum, tobacco and cotton. The forced labour of local people led to their wholesale destruction from disease and overwork.

When Britain began to gain control of the Caribbean from the Spanish 400 years ago (Barbados was captured in 1625, Jamaica in 1655), attempts were made to obtain labour from Ireland and England. English servants could gain free passage to the New World by agreeing to be bound to an employer for a set number of years. They sold their labour in return for their travel costs, food and lodging, and a lump sum at the end of the agreed period.

Around 135,000 indentured servants went out to North America and the Caribbean during the 1600s, often because there was no work available at home. When not enough servants opted for this scheme, more sinister methods were used. Kidnapping of children and young people became common, and political prisoners and religious dissidents were transported to Caribbean plantations instead of prison or execution. As small plantations were merged to create larger ones, even greater numbers of workers who could cope with agricultural work and the tropical climate were needed.

The Society of Merchant Venturers

The Society of Merchant Venturers, which still exists today, began in 1552 as an elite group of Bristol merchants involved in overseas trade. Many of the Members were powerful men because they also held important positions in the Bristol Corporation, the council that ran the city. The setting up of the Society transformed a loose network of traders into a formal organisation to promote trade. The Society petitioned King Edward VI to grant them a charter giving control of all overseas trade from Bristol.

Image: Arms of the Society of the Merchant Venturers

Before 1698 the Royal African Company, a trading company based in London, had control (a monopoly) in Britain on all trade with Africa. With this monopoly, only ships owned by the Company could trade for gold, ivory, wood for dye, spices and traffic enslaved Africans. Any other companies or merchants trading with Africa would have been acting illegally.

The Society of Merchant Venturers in Bristol wanted to get a share of the trade. It repeatedly asked the government to change the rules that allowed the Royal African Company to have total control. In 1698, after much pressure from smaller ports around Britain, such as Bristol, Liverpool and Lancaster, the Royal African Company’s monopoly ended. Later that year Bristol’s first slave ship, the Beginning owned by Stephen Baker, sailed from Bristol to the African coast. The captain purchased a number of enslaved Africans, and delivered them to the island of Jamaica, in the Caribbean. There they were sold and put to work on the plantations.