The personal stories of enslaved men and women were very rarely recorded. Most Africans could not read and write. They came from cultures where writing was not common. Whilst some enslaved Africans learnt to write through their contact with Europeans, it was rare. There are some cases where individuals did learn to write and record their experiences but these are few and far between.

Pero Jones

Pero Jones was born into slavery, as the son of an enslaved African woman on the island of Nevis in the Caribbean. He worked on the sugar plantation belonging to Bristol merchant John Pinney. When John Pinney had inherited this property, he discovered that many of the enslaved African men and women were too old or weak to work, so he sold some of them their freedom. He replaced them with younger, stronger ones, many of them children, whom he could ‘season’ to work.

Among the children he bought in 1765 were Pero and his sisters, Nancy and Sheeba. Pero was about 12 years old. Pinney paid £115 (over £10,000 at today’s value) for the three children and an adult. Pero became Pinney’s personal servant and when the family moved to Bristol in 1783, he came with them. Pero died at the age of 45 years of age, probably still enslaved.

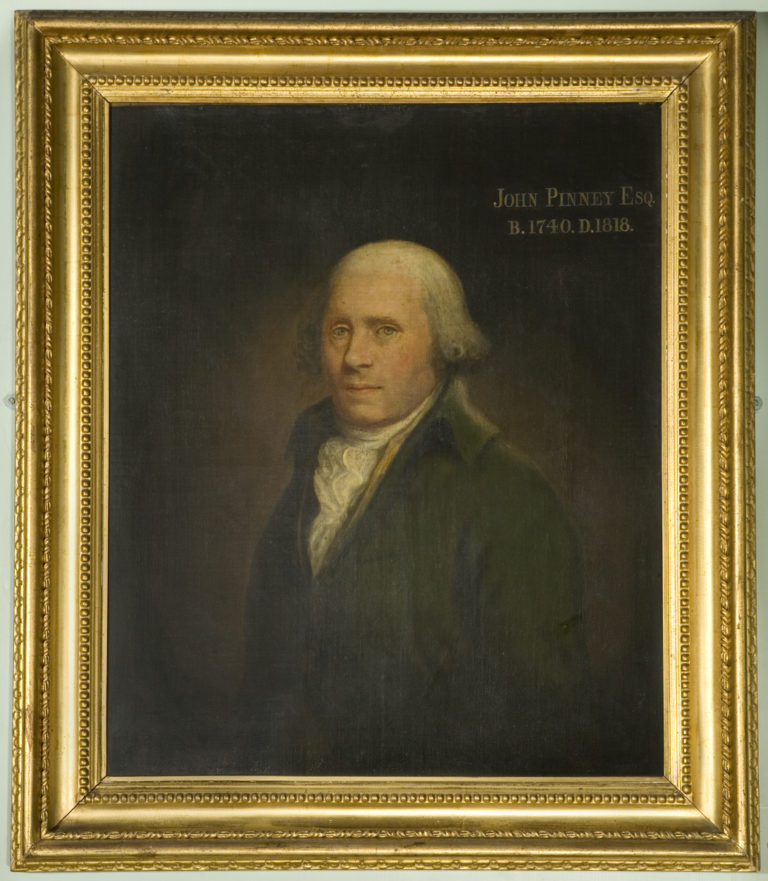

John Pinney

John Pinney, a Bristol merchant, inherited a rundown sugar plantation on Nevis in 1762. He built up the property and by the 1780s at Mountravers, a plantation of 394 acres, there were between 170 and 210 enslaved workers. They produced on average about 110 hogsheads (around 30,000kg) of sugar and around 7,250 gallons (33,000 litres) of rum a year.

Careful management of the plantation, his sugar importing business in Bristol and his investments made him a rich man. When he died he left an estate of £267,000, worth about £15 million today.

Pinney never doubted the need for slavery. In a letter to Mr Harry Pouncy dated 2 March 1765 he wrote:

“Since my arrival I’ve purchased 9 negroe slaves at St Kitts and can assure you I was shock’d at the first appearance of human flesh expos‘d to Sale. But surely God ordain’d ‘em for ye use & benefit of us: otherwise his Divine Will wou’d have been made manifest by some particular Sign or Token.”

After 19 years in Nevis, Pinney returned to Britain and ran his sugar estates through managers.

Between 1789 and 1791, John Pinney commissioned the building of a house in Great George Street, Bristol which is now the Georgian House Museum. He used the study in the house as an office for his firm of Pinney and Tobin, with his business partner James Tobin. They acted as agents for other planters, handling their sugars and arranging for supplies to be sent to them in the Caribbean.

Silas Told

There were some 2,000 sailors who lived in Bristol by the 1750s. Of these, only the most desperate worked on slave ships. This was because illness, terrible heat and the threat of onboard rebellions made the voyages hard. Sailors tried to avoid joining a slaving venture but were often recruited from the rough drinking taverns on Marsh Street, in Bristol by violence or trickery.

Silas Told’s life as an ordinary sailor on a slave ship was a hard one. Told was apprenticed at the age of 14, and badly treated by the captains he sailed under. Sailors not only worked hard managing the ship, but when the captain began to buy enslaved Africans, they also became prison guards whose job was to look after the ‘cargo’.

In the 1750s, Silas Told sailed under Captain Tucker on the Royal George. Tucker was known as a cruel, hard man, and Told suffered whippings and beatings for minor transgressions, as did other members of the crew. His biography records the terrible treatment he and others suffered. He described one whipping, which cut his clothes and his flesh, which was because he had taken too much bread from the stores for dinner one day,

“Captain Tucker went immediately to the cabin, and brought out with him his large horse-whip, and exercised it about my body in so unmerciful a manner, that not only the clothes on my back were cut to pieces, but every sailor on board declared they could see my bones.”

An extract from The Life of Mr Silas Told, Written by Himself, published in 1786